Complex Numbers

by Suraj Rampure

Last modified: March 21, 2019

Before talking about complex numbers, we first need to talk about imaginary numbers. Imaginary numbers stem from the fact that the square root of a negative number is undefined over the set of real numbers – there is no real number $x$ such that $x = \sqrt{-25}$. In order to accomodate square roots of negative numbers, we introduce the imaginary unit $i$.

Foundations

The imaginary unit $i$ is defined by the property

$\boxed{i^2 = -1}$

Often you see $i$ being defined as $i = \sqrt{-1}$, however this notation introduces confusion, as it may imply that $i^2 = \sqrt{-1} \cdot \sqrt{-1} = \sqrt{(-1) \cdot (-1)} = \sqrt{1} = 1$, which is not true. It turns out that the regular radical manipulation rules $\sqrt{xy} = \sqrt{x} \cdot \sqrt{y}$ only apply for non-negative real values of $x$ and $y$.

There is a cyclical nature of $i$ and its powers: $i^2 = -1$, $i^3 = i^2 \cdot i = -i$, and $i^4 = i^2 \cdot i^2 = (-1)^2 = 1$. This pattern repeats: $i^5 = i$, $i^6 = -1$, and so on. (We can formalize this once we learn about modular arithmetic.)

Imaginary numbers, then, are scalar multiples of $i$. Specifically, an imaginary number is a number of the form $bi$, where $b$ is a real number. The imaginary numbers $bi$ and $-bi$ are the roots of the polynomial $x^2 + b^2 = 0$, as $(bi)^2 = (-bi)^2 = b^2 \cdot (-1) = -b^2$, and $-b^2 + b^2 = 0$. The idea of polynomial roots is one we will extend further in the polynomials chapter.

Complex Numbers

The set of complex numbers, denoted by $\mathbb{C}$, is the set of all numbers of the form $a + bi$, where $a$ and $b$ are real numbers and $i$ is the imaginary unit. We say $a$ is the real component of $a + bi$, whereas $bi$ is the imaginary component.

$\boxed{\mathbb{C} = \{ a + bi : a, b \in R, i^2 = -1 \}}$

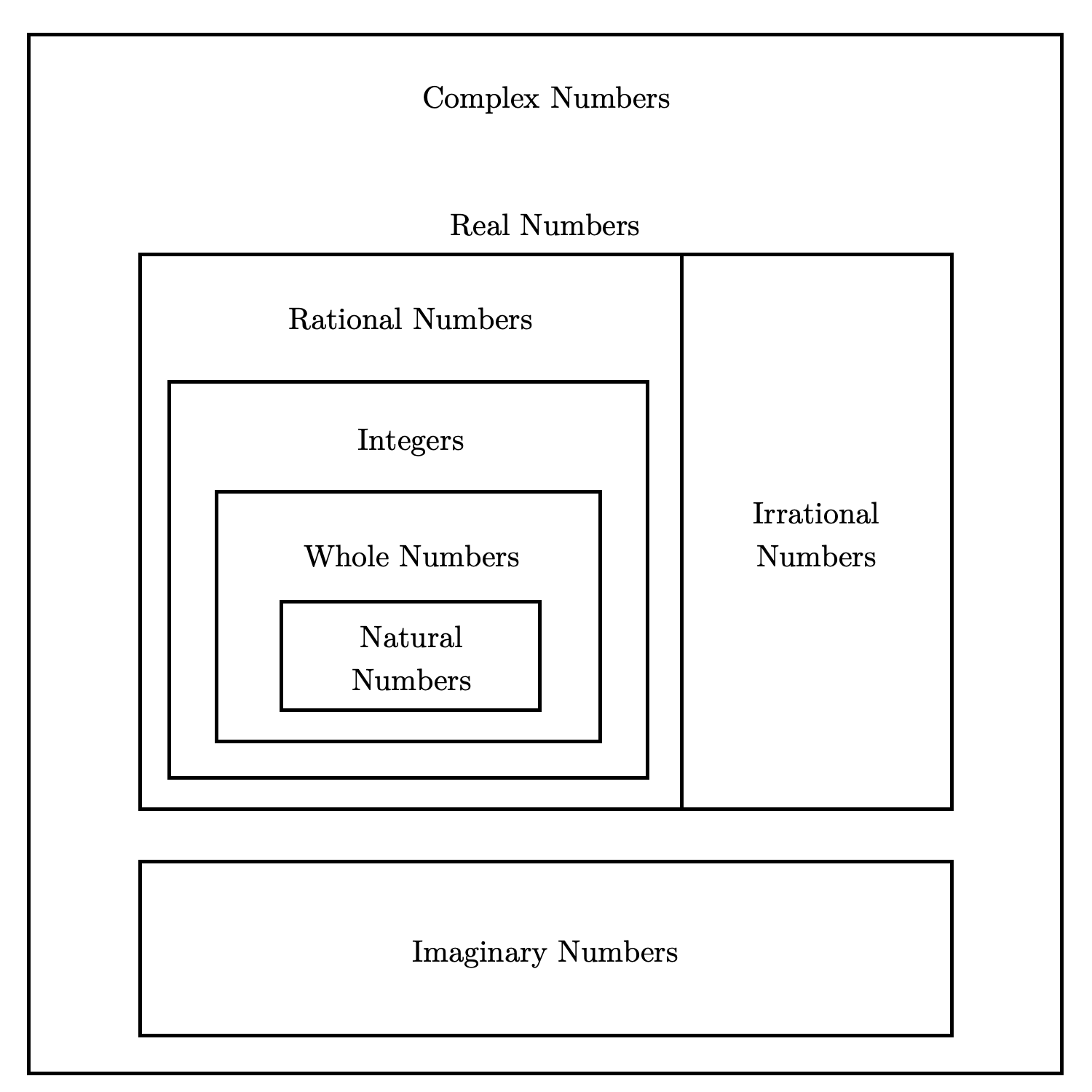

With regards to other number sets, $\mathbb{N} \subset \mathbb{N_0} \subset \mathbb{Z} \subset \mathbb{Q} \subset \mathbb{R} \subset \mathbb{C}$.

This form is known as rectangular form (as opposed to polar form, which is out of the scope of this course). We can easily write any real number as a complex number by setting $b = 0$. We can write any imaginary-only number as a complex number by setting $a = 0$.

The question of whether or not the complex numbers are countable is now simple – since the set of complex numbers is a superset of the set of real numbers, and the real numbers already are not countable, the complex numbers are also not countable.

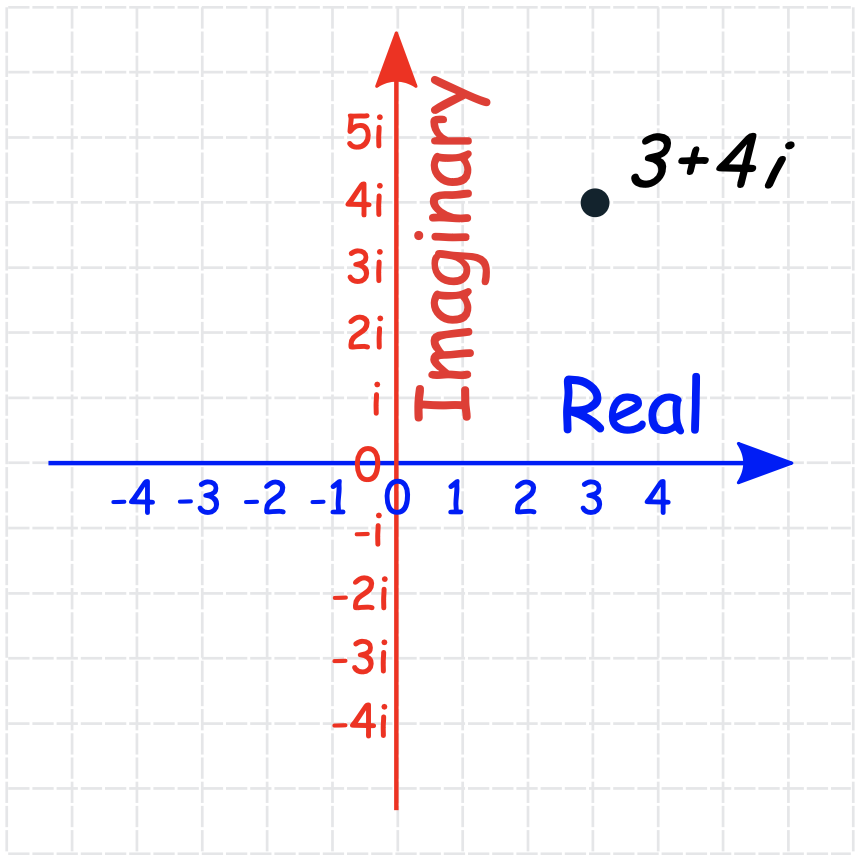

One issue we run into with complex numbers is plotting them – we could represent any real number as a point on the number line, but how do we represent a complex number? For that, we introduce the complex plane (image source).

Perpendicular to the real number line, also known as the real axis, is the imaginary axis. The number $a + bi$ is represented by the point $(a, b)$ in the complex plane, as the example from above shows. Even though the examples all have integral $a, b$, it doesn’t mean that $\pi + \sqrt{5}i$ isn’t a valid complex number – we can plot it just the same.

Complex Arithmetic

We will now look at basic arithmetic operations on the complex numbers.

Addition and Subtraction

Suppose we have two complex numbers $z = a + bi$ and $w = c + di$. Then,

$z + w = (a + bi) + (c + di) = (a+c) + (b+d)i$

$z - w = (a-c) + (b-d)i$

as you might expect. Notice that the sum of two complex numbers is always complex, but is real only when $b + d = 0$, or $b = -d$.

Multiplication

We can multiply complex numbers just the same:

$z \cdot w = (a + bi)(c + di) = ac + adi + bci + bdi^2 = (ac - bd) + (ad + bc)i$

Notice that the product of two complex numbers is always complex, but is real only when $ad + bc = 0$. For example, suppose $z = a + bi$ and $w = a - bi$: then, the product $zw$ is real. It turns out that there is a special relationship between the given examples of $z$ and $w$.

Definition: Complex conjugate

The complex conjugate of the number $z = a + bi$ is defined by $\bar{z} = a - bi$.

Complex conjugates are defined this way for the following reason:

$ z\bar{z} = (a + bi)(a - bi) = a^2 - abi + bai - b^2i = a^2 - b^2i = a^2 + b^2 $

When multiplying a complex number by its conjugate, the imaginary parts fall out and we’re left with a real number. In particular, this real number $z\bar{z} = |z|^2$ is the square of the magnitude of the complex number, i.e. the squared distance from 0.

The product of two complex numbers may just look like gibberish, but it turns out that an interesting property holds: the magnitude of the product of two complex numbers is the product of the magnitudes of the two numbers – that is, $|z \cdot w| = |z| \cdot |w|$. Let’s show that this is true:

$|z \cdot w| = |(ac - bd)^2 + (ad + bc)^2| \\ = a^2c^2 - 2abcd + b^2d^2 + a^2d^2 + 2abcd + b^2c^2 \\ = a^2(c^2 + d^2) + b^2(c^2 + d^2) \\ = (a^2 + b^2)(c^2 + d^2) \\ = |z| \cdot |w| $

This result is part of a theorem known as De Moivre’s Theorem, which we won’t talk about here, but you may research for your own pleasure. (In fact, we actually prove De Moivre’s Theorem to be true in the induction note.)

Division

Conjugates allow us to perform division with complex numbers. Again, consider $z = a + bi$ and $w = c + di$. Then:

$\frac{z}{w} = \frac{a + bi}{c + di} = \frac{a + bi}{c + di} \cdot \frac{c-di}{c-di} \\ = \frac{(ac + bd) + (bc - ad)i}{c^2 + d^2} \\ = \frac{ac + bd}{c^2 + d^2} + \frac{bc - ad}{c^2 + d^2}i$

We used the fact that $w \cdot \bar{w}$ simplifies to a real number in order to simplify the quotient.

Connection to Set Theory

Here is a more complete diagram depicting the sets we’ve learned about in this course:

There is a lot more to complex numbers than we described here; this introduction is far from complete. However, for the purposes of our course, this will suffice.