Sets of Numbers

by Suraj Rampure

Last modified: March 21, 2019

We will now put together our knowledge of set theory and of functions and bijections to formally study the sets of numbers that we use everyday.

Think about the order in which numbers are introduced to you throughout your study of mathematics:

- Natural numbers: We first start off by learning the counting numbers – 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and so on

- Whole numbers: We then introduce the idea of the number 0

- Integers: The number line is then extended in the negative direction, to include negative numbers (a common way this is introduced: if you have three dollars and spend four, how many dollars do you have left?)

- Rational numbers: From there, we look at the idea of fractions, that is, integers divided by non-zero integers

- Irrational numbers: This is the first set that isn’t a superset of the preceeding sets (this is an idea we will explore further in this note); irrational numbers are numbers that cannot be written as an integer divided by an integer, such as $\pi$, $e$ and $\sqrt{2}$

- Real numbers: The union of the rational numbers and irrational numbers

- Complex numbers: Complex numbers are usually introduced alongside the quadratic formula, when trying to explain the nature of complex roots; complex numbers are of the form $a + bi$, where $a, b$ are real numbers and $i$ is the imaginary unit defined by $i^2 = -1$

In the previous note, we said that two sets have the same cardinality if and only if there exists a bijection between the two sets. This means, if we can find a bijection between two sets, then they have the same cardinality.

We will use this principle to compare the cardinalities of all of the number sets listed above, starting with the set of naturals.

Natural Numbers

The natural numbers (also known as the counting numbers), denoted by $\mathbb{N}$, are the most primitive numbers; ones that occur trivially in nature that can be used to count a (non-zero) number of things. Formally, we write

$\boxed{\mathbb{N} = \{ 1, 2, 3, 4, … \}}$

That formal definition of the natural numbers leaves something to be desired. However, the natural numbers are the numbers you’ve dealt with for the longest – the set of positive numbers beginning with 1, spaced 1 apart. Note the omission of 0 in this set.

Whole Numbers

The set of whole numbers, denoted by $\mathbb{N}_0$, is the union of the set of counting numbers with the number 0. Formally, we write

$\boxed{\mathbb{N}_0 = \{ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, … \}}$

With regards to other number sets, $\mathbb{N} \subset \mathbb{N_0}$.

Some mathematicians consider 0 to be a part of the natural numbers, hence rendering the above two sets equal. To avoid ambiguity, we will always use $\mathbb{N}$ to refer to the set $\{1, 2, 3, …\}$ and $\mathbb{N}_0$ to refer to the set $\{0, 1, 2, 3, …\}$. Read this for more insight.

Using our definition, though, clearly the set of whole numbers has more elements than the set of naturals – the whole numbers include every single element in the naturals, along with the number 0! However, that does not mean their cardinalities cannot be the same. The question is, does there exist a bijection that maps elements from $\mathbb{N}$ to elements of $\mathbb{N}_0$? If such a function existed, we should be able to pass in the natural numbers, in order, and receive the whole numbers, in some order.

It turns out that such a function does indeed exist. It is the function $f: \mathbb{N} \rightarrow \mathbb{N}_0$ given by $f(x) = x - 1$.

Let’s see if it checks the boxes:

- Injective: Do two elements in the domain ever map to the same element in the codomain? No, but as justification, let’s suppose they did. Let $a$ and $b$ be two unequal ($a \neq b$) natural numbers that map to the same whole number under this function. That would mean $a - 1 = b - 1$, but by adding 1 to both sides we see that $a = b$. This contradicts what we assumed earlier, so that doesn’t make sense. (Such a justification is overkill, but it’s good to start thinking formally as we start studying proofs in the next chapter.)

- Surjective: Does every element in the codomain $\mathbb{N}_0$ get mapped to? Yes – in fact, if we let $n$ be some element in $\mathbb{N}_0$, the number pointing to it from $\mathbb{N}$ is precisely $n + 1$, because $f(n+1) = n$, as required.

Therefore, $f: x \mapsto x - 1$ is indeed a bijection from $\mathbb{N}$ to $\mathbb{N}_0$, therefore the two sets have the same cardinality.

Notice, as we pass in consecutive elements of $\mathbb{N}$: 1, then 2, then 3, then 4, and so on – we get consecutive elements of $\mathbb{N_0}$: 0, then 1, then 2, then 3, and so on. Sets have no inherent order, but since there is no largest element in either $\mathbb{N}$ or $\mathbb{N} _ 0$, it doesn’t really make sense to start counting from anywhere else. By finding a bijection to map between the two sets, we are essentially finding an ordering of the second set – $f(1)$ is the first element, $f(2)$ is the second element, and so on. The following is a result of this interpretation:

Definition: Countably infinite

We say set $S$ is countably infinite if and only if there exists a bijection from the natural numbers (or any other countably infinite set) to $S$. If such a bijection does not exist, we say $S$ is uncountably infinite.

One way to think of this is to give each number a waiting number in an infinitely long line (credits to homeschoolmath.net for that analogy).

Since the natural numbers and whole numbers both have the same cardinality, and the natural numbers are the basis for countability, the whole numbers are also countable. Showing that a set has a bijection with the whole numbers is the same as showing it has a bijection with the natural numbers; either works in showing the countability of a set. We will use the idea of countability to examine the sets that follow.

An important note: Just because there exists a bijection between $\mathbb{N}$ and $\mathbb{N_0}$ doesn’t mean that every single function between these two sets will be a bijection. For instance, I can create the function $f: \mathbb{N} \rightarrow \mathbb{N}_0$ given by $f(n) = 2n$. This is a perfectly valid function that takes in elements of the naturals as inputs and returns an element of the wholes. It is not a bijection, though, because for instance the whole number $3$ is never seen as an output.

Integers

The set of integers, denoted by $\mathbb{Z}$, is the union of the whole numbers with their negatives. Formally, we write

$\boxed{\mathbb{Z} = \{ …, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, … \}}$

With regards to other number sets, $\mathbb{N} \subset \mathbb{N_0} \subset \mathbb{Z}$.

You should be asking yourself – are the integers countably infinite, or uncountably infinite?

It turns out that they are indeed countable, but finding the bijection isn’t so obvious. We need a function that, as we plug in successive natural (or whole) numbers, gives us successive integers. However, unlike the jump from naturals to whole numbers, where we just added one new element, we now added infinitely many numbers in the negative direction of the number line. It wouldn’t make sense to attempt to count all numbers greater than or equal to zero, and then somehow start counting the numbers less than zero – we need to find a way to count positive and negative integers at the same time, systematically. We can do so by writing the set out in a clever way (which we can do, since sets do not change based on their ordering), with the whole numbers listed above:

| $\mathbb{N}_0$ | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $\mathbb{Z}$ | 0 | 1 | -1 | 2 | -2 | 3 | -3 | 4 | -4 | 5 | -5 |

What do we notice?

- Every integer corresponding to an even whole number is exactly half of the whole number, but negative

- Every integer corresponding to an odd whole number is exactly half of the next largest whole number

We can encapsulate that behavior into the following function, which you can verify independently to be a bijection:

$ f(x) = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} -\frac{x}{2} & x \: \text{is even} \\ \frac{x+1}{2} & x \: \text{is odd} \\ \end{array} \right. $

As we plug in consecutive values of whole numbers beginning with 0, we get an ordering of the integers. This isn’t the only possible ordering: we could count from 0 to 10, then -1 to -10, then 11 to 20, then -11 to -20 (and so on and so forth), and find a bijection (albeit complicated) that returns the integers in that order. We just happened to choose a simpler bijection and a more natural ordering.

Rational Numbers

The set of rational numbers, denoted by $\mathbb{Q}$, is the set of all possible combinations of one integer divided by another, with the latter integer being non-zero. Formally, we write

$\boxed{\mathbb{Q} = \{ \frac{p}{q} : p, q \in \mathbb{Z}, q \neq 0\}}$

With regards to other number sets, $\mathbb{N} \subset \mathbb{N_0} \subset \mathbb{Z} \subset \mathbb{Q}$.

Before we state whether or not the rationals are countable, let’s investigate an interesting property that they have.

Definition: Dense order

We say a set $S$ is densely ordered if $\forall a, b \in S, \exists : c \in S : a < c< b$.

In English, this condition states that between any two elements in a set, there is some other element in the set that is between the first two.

We wrote the set of rational numbers symbolically slightly differently than we wrote the sets that preceeded it – we had to specify a rule to generate rational numbers (i.e., we used set-builder notation). There’s no one concrete ordering of all rational numbers, because the rational numbers are densely ordered – between any two rational numbers, there are infinitely many other rational numbers! To see this fact, consider two rational numbers $a$ and $b$. Since both are integers divided by integers, $\frac{a}{2}$ and $\frac{b}{2}$ are also rational, and the rational number $\frac{a}{2} + \frac{b}{2} = \frac{a+b}{2}$ is also rational, and in between $a + b$ – it is the average of the two numbers. This is in constrast to the integers, where in between any two integers, there are only finitely many integers (in fact, if $n$ and $m$ are two integers numbers, such that $m > n$, then there are $m - n + 1$ integers in between, including both $n$ and $m$).

The question remains, is the set of rational numbers countable or uncountable? The fact that there are infinitely many rational numbers in between any two rational numbers may lead you to believe that the set is uncountable, but in fact, the rationals are still countable!

Recall, we previously said that if $|A| \geq |B|$ and $|A| \leq |B|$, where $A$ and $B$ are two sets, then $|A| = |B|$. We also saw that if there exists an injection $f: A \rightarrow B$, then $|A| \leq |B|$. Our problem now boils down to showing that $|\mathbb{N}| \leq |\mathbb{Q}|$ and $|\mathbb{Q}| \leq |\mathbb{N}|$.

Without much work, we can identify that $|\mathbb{N}| \leq |\mathbb{Q}|$, since $\mathbb{N} \subset \mathbb{Q}$. If we want to be more formal, though, we can explicitly find the injection from $\mathbb{N} \rightarrow \mathbb{Q}$ – consider the function $f: \mathbb{N} \rightarrow \mathbb{Q}$ given by $f: n \mapsto n$. This function will never map two natural numbers to the same rational number, thus it’s an injection, confirming our intuition that $|\mathbb{N} \leq |\mathbb{Q}|$.

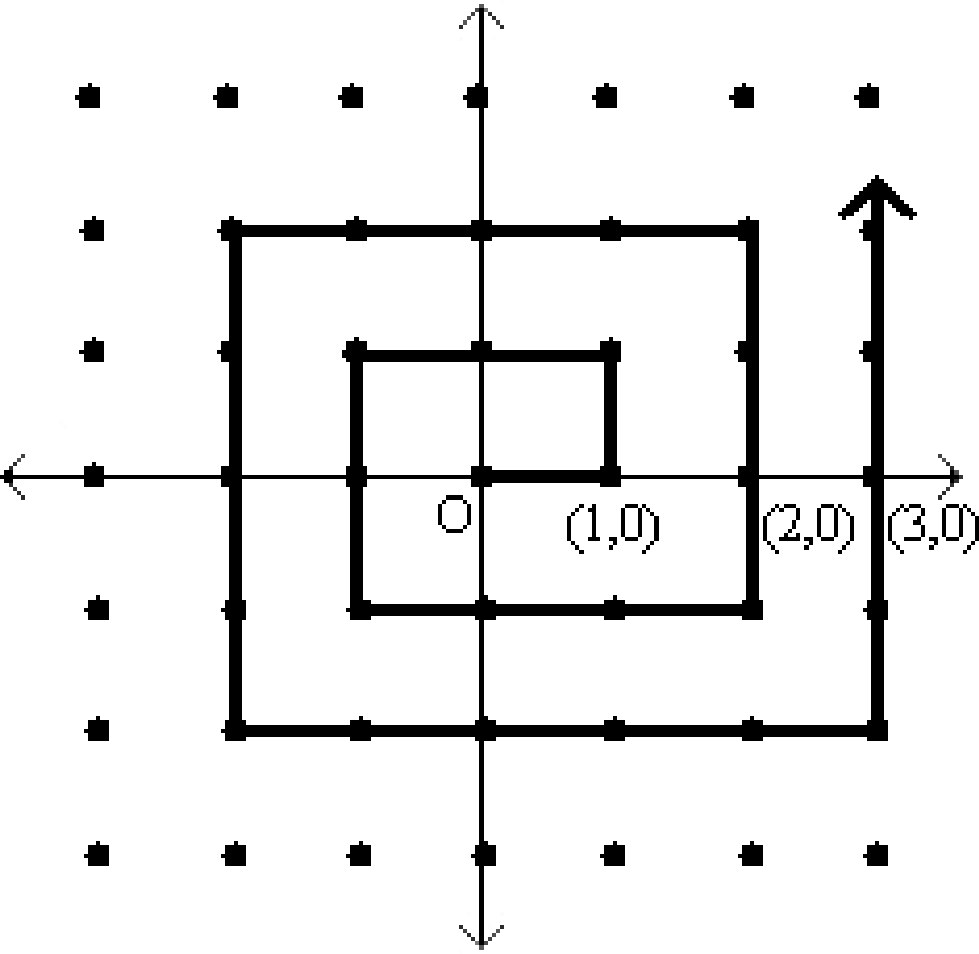

We need to show an injection in the opposite direction, i.e. a function from the rationals to the naturals such that no two rationals map to the same natural number. Consider the following diagram (taken from the CS 70 notes):

Suppose each point $(x, y)$ represents the rational number $\frac{y}{x}$. Then, this path will eventually hit every single rational number, no matter how large its numerator and/or denominator are. The output value of each point is its “position” in the spiral path. As well, not every point is a valid point:

- every point on the y-axis is invalid, as the x-coordinates are all zero, and thus are of the form $\frac{y}{0}$ (except $\frac{0}{0}$, which we can arbitrarily set to be the number 0)

- the points $(3, 4), (6, 8), (9, 12)$ all represent the same number ($\frac{4}{3}$) – in order to remove duplicates in our domain, we only count the first valid occurrence of each rational number

Then, our injection $\mathbb{Q} \rightarrow \mathbb{N}$ looks something like this:

| $\mathbb{Q}$ | $0$ | $1$ | $-1$ | $-\frac{1}{2}$ | $\frac{1}{2}$ | $2$ | $-2$ | $-\frac{2}{3}$ | $-\frac{1}{3}$ | $\frac{1}{3}$ | $\frac{2}{3}$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $\mathbb{N}$ | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

This relationship is certainly a function, because every rational number appears somewhere along this spiral (exactly once, because we only count unique occurrences). This is certainly an injection, as no two rational numbers are at the same position in this spiral.

Since the above function is an injection, we have that $|Q| \leq |N|$. From before, we had that $|N| \leq |Q|$, therefore we have (from the above theorem) that $|Q| = |N|$. Therefore, the rational numbers are indeed countably infinite.

Real Numbers

The set of real numbers, denoted by $\mathbb{R}$, is the set of all possible distances from 0 on a number line. The real numbers can be divided into two groups – rational numbers (as defined above), and irrational numbers. Formally, we say

$\boxed{\mathbb{R} = \{ 3, \pi, -\sqrt{63}, 0.1224, \frac{2}{3}, … \}}$

With regards to other number sets, $\mathbb{N} \subset \mathbb{N_0} \subset \mathbb{Z} \subset \mathbb{Q} \subset \mathbb{R}$.

For the sake of completeness, we define the set of irrational numbers below.

Definition: Irrational numbers

The set of irrational numbers, denoted by $\mathbb{R} - \mathbb{Q}$, is the set of real numbers that are not rational. That is, they are real numbers that cannot be written as an integer divided by another integer. Formally, we say $\boxed{\mathbb{R-Q} = \{ \pi, -e, \sqrt{5}, … \}}$

With regards to other number sets, $\mathbb{R - Q} \subset \mathbb{R}$. It should be noted that $\mathbb{R - Q}$ is the first set we’ve studied that is not a superset of the sets that we studied before it.

Once again, we are faced with the question – are the real numbers countable? After all, like the rational numbers, the reals are densely ordered – between any two real numbers are infinitely many more real numbers. Surely, the reals have the same countability as the rationals?

It turns out they do not. There is no ordering of the real numbers. There is no bijection between the natural numbers and real numbers. The proof for this requires slightly more mathematics than we’ve covered so far in the course. If you’re interested in reading the proof that the reals are not countable, known as “Cantor’s Diagonalization”, feel free to read it on the CS 70 website.

The proof for this comes in the form of a counterargument. We’ve yet to formally study proofs, but this argument is what is known as a “Proof by Contradiction” – we will start off by assuming that the real numbers are countable, and through a series of valid steps, we will arrive at a contradiction, telling us our initial assumption was wrong. Since our initial assumption will be that the real numbers were countable, this will tell us that they are not countable.

Summary

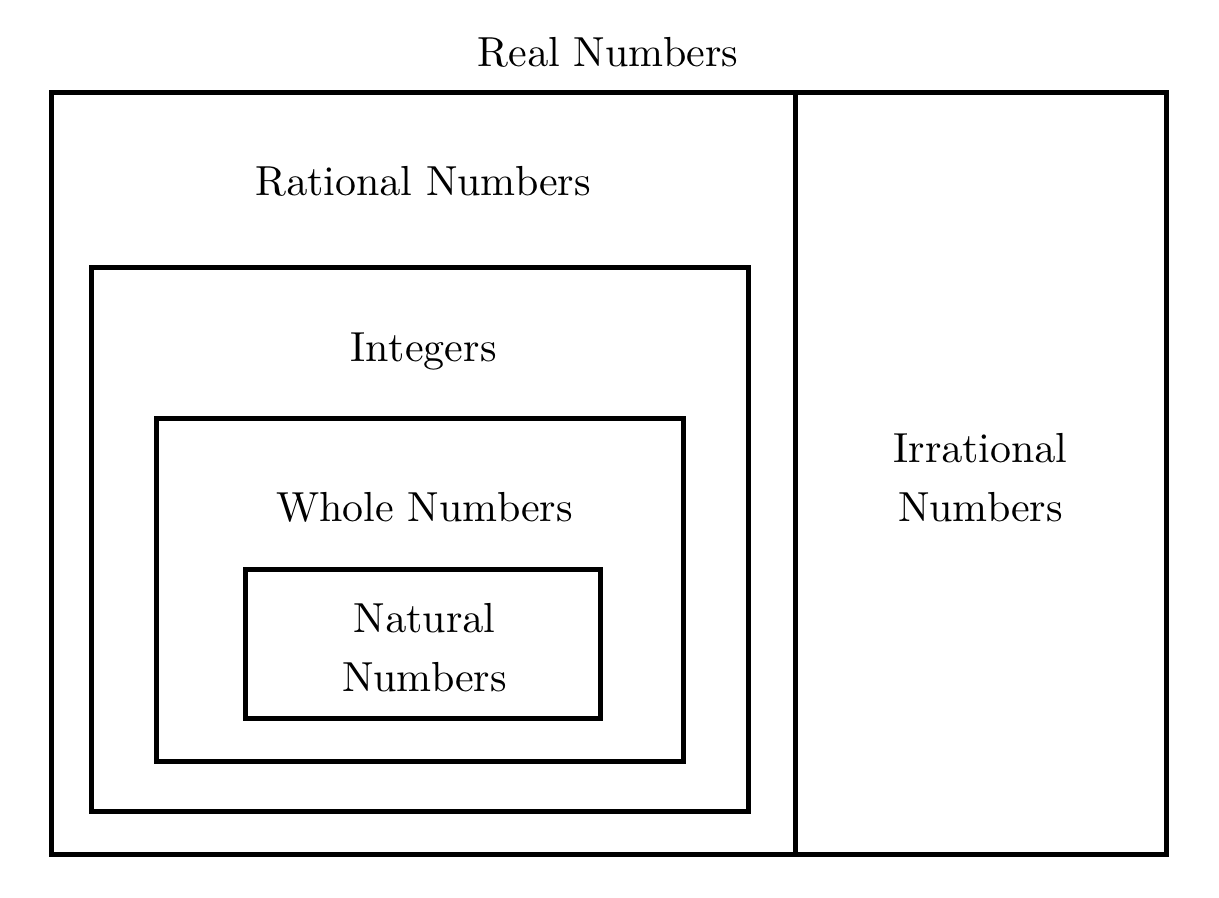

The following diagram summarizes the hierarchy of the number sets we’ve studied thusfar:

A more complete version of this picture is painted in the complex numbers note.

Bonus: Transcendental Numbers

(Note: At least in the accompanying course at UC Berkeley, we won’t be studying transcendental numbers very much. We define them just to make you aware of their existence.)

We say a number is transcendental if it is not the solution to a non-zero polynomial equation with integer coefficients. In other words, $t$ is transcendental if there are no $a_0, a_1, …, a_n$ such that $a_nt^n + a_{n-1}t^{n-1} + … + a_1t + a_0 = 0$.

Common examples of transcendental numbers are $\pi$ and $e$. On the other hand, while $\sqrt{2}$ is irrational, it is not transcendental, as it is a root to $x^2 - 2 = 0$.

No rational number is transcendental; if $m = \frac{a}{b} \in \mathbb{Q}$, we have that $m$ is a solution to $bx - a = 0$. As a consequence, all real transcendental numbers are irrational, but transcendental numbers can also be complex. If a number is not transcendental, i.e. if it is the solution to a non-zero polynomial with integer coefficients, we call it algebraic.